My Congo Years: Part 2. All aboard the Benguela Railway.

Three Days by steam across Africa into the heart of the Copper Belt.

In August 1949, after a year in Belgium, we sailed south to the continent that would shape everything. From cordite in Tenerife to Neptune’s court on the Equator, then landfall at a port in Angola, and steam eastward onto a savannah plateau and into the Belgian Congo’s copper-rich Katanga Province. This was the journey that began my Congo childhood.

This excerpt from my unpublished memoir picks up the story—dust, steam, and a first glimpse of Savannah Country.

An earlier era’s CMB poster with ours a 1928 10,000-Ton paquebot, or mail vessel, with a stop only in Tenerife enroute to the Angolan port of Lobito, and then to the Belgian Congo’s port of Matadi up from the mouth of the Congo River.

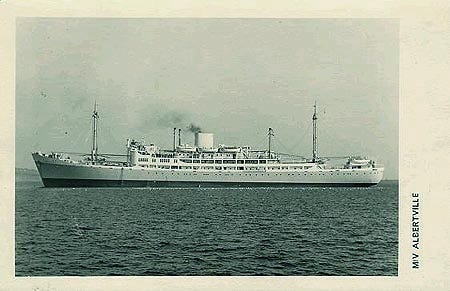

In August 1949, we were finally enroute to the so-called Mission Field. We were on board the MV Albertville—one of the Compagnie Maritime Belge’s (CMB) 10,000-Ton paquebots, each named for a city in the Belgian colony—we sailed on their regular Congo run. Our 18-day run from Antwerp was headed for the port of Lobito in Portuguese-ruled Angola with a stop-over in Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands.

Tenerife was dry and dusty. Volcanic. We toured in an open car high above the port of Santa Cruz, then returned to a bright mid-day in a cathedral square. A loud explosion. The smell of cordite. A split-second later, a single black shoe landed flat and noisily on the cobblestones in front of us. That image has never left me. Was someone killed that day? Or just having fun? A festival perhaps. The second shoe never dropped.

The MV Albertville dated from 1928 and was later joined by the likes of the Elisabethville (1949), Charlesville (1951), and Baudouinville (1958) which were larger, sleeker, and more modern—part of Belgium’s postwar effort to reassert its colonial presence which ended chaotically in 1960 with the Congo’s sudden independence.

A few days later, as we crossed the Equator, Father Neptune climbed out of the sea and set up court beside the Albertville’s swimming pool. The smell of grease and wet rope. Sloppy pastel paints. Noise. Clangs. Punishments meted out. Passengers tumbling off a greasy plank into the green-coloured pool. I believed it all. And cringed the entire time.

Shortly afterwards, we were finally in Africa. With our collection of footlockers safely on the dock and the SS Albertville heading north to Matadi—up the mouth of the mighty Congo River—we spent a night at Lobito’s Hotel Terminus before boarding our wood-fired steam train the next day for the slow eastward run across the Portuguese West African colony—and half of central Africa—to our destination, the Belgian Congo’s Katanga province.

I remember the excitement of a great journey underway. Noise and smells. Someone took a picture of the five of us grinning broadly in our white colonial pith helmets under the harsh mid-day sun.

Dad had proudly scored a couple of empty, wicker-covered demijohns with oversized handles—normally full of Portuguese red wine, of course—and filled them with drinking water for the journey ahead, bashing their huge corks home. (Methodist ministers weren’t allowed to drink alcohol in those days.

Then came that steep climb for a nearly six-year old—up the metal steps into the musky-smelling wooden passenger carriage, along a narrow walkway with louvered windows, and into our two compartments. The pith helmets were stashed on the overhead rack high above the seats.

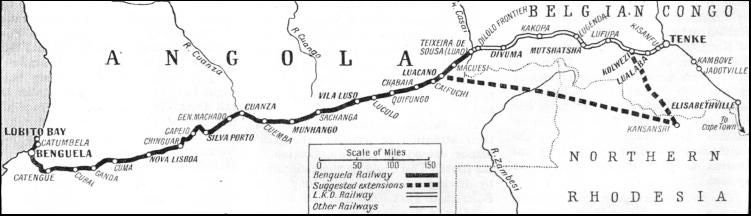

We were on the Benguela Railway, which ran for roughly 2,000 kilometres from Lobito Bay—south of the Portuguese colony’s capital, Luanda—up onto the eastern Angolan plateau and into the Congo’s mineral-rich Katanga Province, part of the Copper Belt straddling the border with then-Northern Rhodesia, today’s Zambia.

The railway—later destroyed in the Angolan Civil War after 1975 and later rebuilt with Chinese funding—was Katanga’s main export link to the world, mostly copper. (Another line for Katanga’s lucrative copper exports ran south through the two Rhodesias and into South Africa.)

With frequent stops for wood and water and hardly all that fast, our rail journey took a good three days. We were also at the end of the dry season (April to September), when temperatures peaked before the rains returned. Pungent smoke and soot from the wood-fired steam engine swirled through the carriage. I was fascinated at one impromptu stop where, using a ladder, train workers scrambled up a telegraph pole to tap out a Morse Code message to the station ahead.

Waking up on the first morning, I ratcheted up the louvered window to a landscape of grasslands, scattered trees and distant hills—eastern Angola’s Savannah Country. We clattered over a steel-girded bridge where the mud-coloured water barely flowed far below the banks. Everything was dry and dusty. Pale greens, yellows and browns. I was entranced. That first glimpse of Africa’s savannah has stayed with me—a dry, open stillness I’d meet again in Vietnam, and later Australia.

But as temperatures rose and the second day dragged on, I got bored and restless. While my parents stretched out for their first tropical siesta, my eyes wandered languidly up to those pith helmets on the overhead rack. Mom had given express instructions to us kids not to touch them until we reached the Congo.

Not me. In an early display of contrariness, I reached up, grabbed mine, plunked it on my head, and strutted out into the passageway. Through the open windows and smoke, I gazed out at the endless savannah. Then, as we passed thicker vegetation right alongside the tracks, I casually poked my head out the window. In a split second, the wind whisked my white pith helmet off my head. Oops.

I still vividly remember the fright and panic as I reached out. But too late. For an eternity, my pith helmet wafted through the air, flipped over a couple of times flashing its lovely leather straps and green silk lining, before crashing to the ground, bouncing along and going into a roll. An African kid rushed out from the trackside village and grabbed it. There went my White Man symbol.

As I sheepishly confessed my transgression, I braced for severe punishment. But there was no lecture. No scolding. Just the first guilt trip I can remember from my mother, who—once in the Congo—adopted the Swahili expression kazi yako (literally “your work”) as her own. You mess up, kid, and you live with the consequences. Mine? The daggiest collection of replacement hats imaginable.

During the night, we crossed into the Belgian Congo at the border town of Dilolo. My mother’s notes recall how moved they were by other missionaries who drove hours down dirt roads from the up-country Methodist missions at Sandoa, 80 kms to the north, to welcome us—but we children were fast asleep.

Our destination lay 400 kms further east: Jadotville (now Likasi), the colony’s third-largest city after Leopoldville (Kinshasa) and Elisabethville (Lubumbashi). We arrived at mid-day, met by the missionary family we’d replace, and were driven to our new home—a just-completed three-bedroom brick structure, still smelling of cement, whitewash, and enamel.

The main street of Jadotville even had a Ford dealership where my father would later purchase a car for his mission work around the Katanga. The railway station is at the end of the street. I still remember its entire lay-out.

With a population of around 50,000, Jadotville was a modern copper-smelting centre perched on the 1000-meter-high Katanga Plateau—one of the richest mineral lodes in the world. Besides copper, the region held manganese, zinc, cobalt, and other exotic minerals.

And ironically, given what had motivated my parents to become missionaries in the first place, the uranium for America’s first atomic bombs—the two dropped on Japan—came from the nearby Shinkolobwe Mine. With all this mineral wealth, Katanga was also the most developed of the Belgian Congo’s six provinces.

While the steaming rainforests of the Congo River Basin dominate most of the country, we were on a high savannah plateau backed by rugged ranges marking the watersheds of that river—here called the Lualaba—and the Zambesi, with its famous Victoria Falls, to the south.

Early explorers believed the Lualaba was the source of the Nile. But as the river reaches Stanleyville—today’s Kisangani—north of the Equator, it becomes the Congo River, veers westward, and loops its way into the so-called Bas-Congo, past then-Leopoldville, the port of Matadi, and into the Atlantic Ocean at Boma, where the country’s coastline is barely 60 kms wide.

On the southern side of the Katanga Plateau, the Zambesi River runs southeast along the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe—formerly Northern and Southern Rhodesia—where the Falls are located, and then through then-Portuguese East Africa, or Mozambique, into the Indian Ocean.

In Jadotville, we were about 11 degrees south of the Equator—roughly the same latitude as Darwin, Australia—with a Dry Season (April to September) and a Rainy Season (October to March). And as we’d soon discover, winters in the Katanga—especially around July and August—could be downright chilly. Our new home even had a fireplace.

Our brand-new four-bedroom home still smelled of cement, whitewash and enamel when we arrived in 1949.

The next four years in Jadotville, from the age of six to ten, were the happiest of my life—and certainly the most stable until I finally settled in Australia in the 1970s. But only when I returned to the Congo in late 1997 did I realise just how crucially formative those years had been. My lack of racial prejudice. Judging people by their eyes.

The Congo is also where I developed my lifelong curiosity and detailed memory for place. Even now, I can picture the town’s entire physical layout in my head.

A shallow cutting from the west brought trains into Jadotville’s stone-faced, corrugated-roof railway station (now relocated). Just before it, a metal bridge crossed over and dipped into the Quartier Mission, where our sizeable compound sat just to the left. I grew up to the sounds of steam trains shunting in and out, whistles echoing across the valley.

Along the unpaved road in front of our house, the last purple jacaranda blossoms—Brazilian natives and my lifelong favourites—were falling. Soon, a dark-leafed acacia burst into yellow bloom along the side road paralleling the rail line. Then came the red flamboyants, or poinsianas—the same sequence I’d later find in Queensland. Behind the house, a huge mango tree, just coming into bloom, anchored the yard. A driveway entered the compound, flanked by guava trees. Further along the boundary stood a line of fully-grown eucalypts—Australian natives, of course—whose flammable nature I’d discover soon enough.

Congolese gather in welcome in the main part of our Methodist mission compound in the copper-smelting town of Jadotville in the Katanga with our home, pictured above, behind us. They were taught literacy, sewing and other skills.

Diagonally across from our compound stood a large, older residence occupied by a sullen Methodist missionary family from Finland. Their property included a garage-like structure with several improvised classrooms attached, used to teach Congolese adults—both men and women.

Jadotville—named after a Belgian mining engineer who never set foot in the Congo—was a company town run by the Anglo-Belgian mining giant Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, or simply l’Union Minière (UMHK).

Later infamous for backing Katanga’s secession after Congo’s tumultuous independence in 1960, UMHK helped trigger a massive United Nations intervention—and, in 1961, the death of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in a still-haunting air crash at Ndola, just across the North Rhodesian border.

Looming to the south, Mount Likasi stood alone—a solitary hill with a vast open-pit copper mine carved into its eastern flank. On the northern side, a sloping galvanized tin structure, studded with chimneys, housed the smelter, which ran day and night. At night, when the copper ingots were poured, the entire complex lit up in molten red, and clanging echoes rumbled across the shallow valley below our home.

Across the front road lay the marshalling and maintenance yard of Katanga’s vital rail link to the outside world: the Chemin de Fer Bas-Congo Katanga (BCK). Despite its name, the BCK didn’t connect Katanga directly to the Lower Congo. Instead, it ran northwest to Port Francqui—today’s Ilebo—where, as Le Voie National, passengers and cargo continued by river: first the Kasai, then the Congo River, down to Leopoldville. From there, the other end of the BCK descended through a precipitous mountain range to the port of Matadi—a route more than twice as long as the run through Angola. Given the colony’s woeful roads, the BCK and its river links were its true lifeline.

Already fluent in the French alphabet, we picked up the local acronyms—and their weight—in no time. (Just try saying UMHK the French way. It sticks.)

Coming up in Part 3: The Belgian colony, our uneasy but vital place in it—and back to school, in French of course. Oh, and learning Swahili from Congolese playmates.